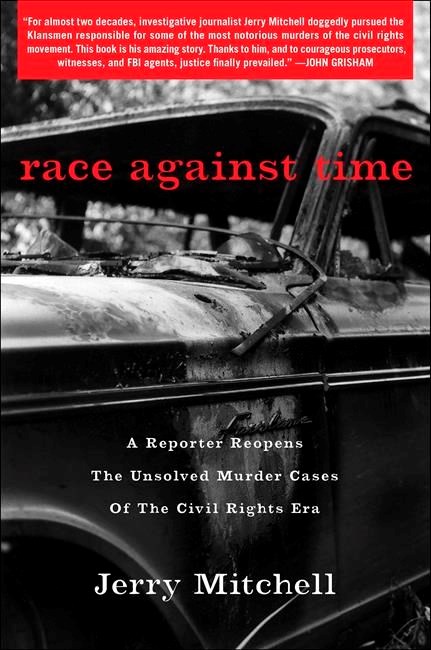

"Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era,” Simon and Schuster, by Jerry Mitchell

As the court reporter for the Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi, Jerry Mitchell developed an obsession with four of the most notorious civil rights cases of the 1960s, including the murder of Medgar Evans on his front yard and the killing of three civil rights workers. But witnesses had died, memories had faded and documents had been destroyed. Finding enough evidence to reopen cases seemed like a worthy but impossible mission.

Mitchell pursued these cases on his own initiative, sometimes straying outside his editor’s guidelines and often thoroughly frightening his wife by, for example, visiting suspected killers at their houses, in remote areas, after sundown. As Mitchell’s stories revealed more and more information on the cases, district attorneys took note and ultimately brought indictments.

This time, jurors convicted those whose crimes has been unpunished for decades.

Mitchell’s work deserves applause for his tenacity in bringing justice where the system failed miserably. His work also highlights the value of high-ideals journalism in a democracy. Were he reporting in Washington or New York, Mitchell would be a nationally renowned journalist, mentioned in the same sentence as Woodward, Bernstein and Hersh.

But Mitchell’s

In the cases he chronicles here, the degree of sheer evil and overt corruption was numbing. Police officers were Klansmen. Witnesses were threatened. Jurors were coerced. The guilty were celebrated. Bible passages were invoked for justification of murdering blacks and civil-rights workers.

Several of the characters in Mitchell’s book implored him to let the past go, forget it, move on. “Let it rest” is code for “yes, we did terrible things but we’re a better people now so can we not talk about the past?”

But as the pain of families of the murdered shows, justice denied cannot rest. Imprisonment of old men for long-ago killings may not have changed multitudes of hearts and minds, but if better angels are to prevail, a society must reconcile its past.

Mitchell does that in this book.

And he’s not stopping either. He’s the founder of the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, which is pressing on with, as Mitchell says, “reporting that makes a difference.”

Jeff Rowe, The Associated Press