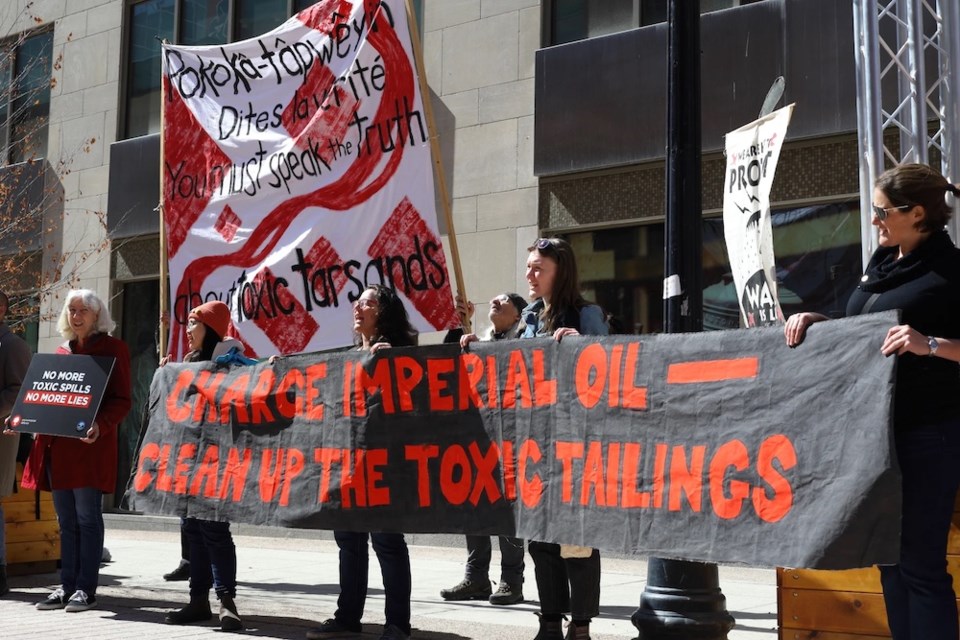

Nine charges against Imperial Oil were laid Friday over a toxic spill in northern Alberta. The charges by the province’s energy regulator mean the company could face fines ranging from a slap on the wrist to serious deterrence.

The charges date back to 2023 when 5.3 million litres of toxic waste from Imperial’s Kearl Oil Sands Processing Plant were released into the environment. The massive spill revealed the facility had been seeping for months before downstream Indigenous nations were notified. The spill led to a $500-million lawsuit against the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) by the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation.

Now, the nine charges arrive two weeks after the publication of a report that found the AER only inspected three per cent of reported tailings spills, publicly reported data is false and incomplete, and the regulator has been unforthcoming about the two spills from Imperial’s Kearl oilsands mine, claiming there are no environmental impacts.

Alienor Rougeot, climate and energy program manager at Environmental Defence, told Canada’s National Observer, that it’s a good thing the charges have been laid, but the move doesn’t reflect a new era of accountability in Alberta. If pressure from the media and civil society suddenly went quiet, the regulator would return to “old habits of turning a blind eye to pollution.”

“I think the [Alberta Energy Regulator] is feeling the heat right now, in terms of Albertans and Canadians more broadly, demanding that it be an effective regulator,” Rougeot said. “I think this is a response to that.”

For critics like Rougeot, the continued weakness of the AER points to evidence of a captured regulator.

In an interview with Canada’s National Observer, Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam continued to call for an overhaul of the AER.

Adam sees the fossil fuel industry represented at the highest levels of the regulator, which has compromised its integrity.

“It wasn't meant to protect anybody from Alberta — it was meant to protect the industry, to make sure that everything was kept hidden,” Adam said.

He calls for a more diverse representation on its board, including community members, environmental science experts and other stakeholders who care for people living downstream.

Adam and Rouegot agree that not only does there seem to be a captured regulator in Alberta, but also a captured legislature.

“These things [have] got to be answered, instead of running off to Mar-a-Lago to meet with Donald Trump,” Adam said of Premier Danielle Smith.

“Where's her responsibility here in Alberta, and if she's out there to give more oil for free, how's she going to do it with a broken regulatory system here in Alberta that's not working?”

The regulator’s charges were not attached to specific fines, but it has come under fire recently for issuing weak penalties. Only last August, the regulator was denounced by experts and critics over a $50,000 administrative penalty, which it claimed was the maximum allowed under the Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act. Experts told Canada’s National Observer at the time that the penalty was more than 95 per cent lower than it could have been.

Six of the nine current charges have also been laid under the Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act, which carries a maximum administrative penalty of $5,000 a day. The three other charges are under the Public Lands Act, which carries fines ranging from $60 to $600, depending on the offence. In some cases, there is no specified penalty amount.

Martin Olsynski, an energy law professor at the University of Calgary, says he has heard that Imperial’s first appearance next month will be in Alberta’s Court of Justice, “essentially like a small claims court” with a cap of $100,000.

“Does that mean the AER is not looking for fines in excess of $100,000?,” Olsynski said in a phone interview with Canada’s National Observer. “I don’t know the answer to that, but I think it is certainly something worth asking the AER.”

Canada’s National Observer asked the regulator if the fines could amount to $100,000 or less, or if the charges could proceed to a higher court where fines can be elevated. The Alberta Energy Regulator did not answer the questions by the publication deadline.

In a separate statement, the regulator told Canada’s National Observer that it “remains diligent and proactive in monitoring compliance and addressing infractions to ensure the safety of the public and the protection of the environment.

“As this is a matter before the courts, the AER is not able to provide further details,” the statement continued.

In another statement, Imperial Oil told Canada’s National Observer it received notice of the charges and will review next steps. Imperial also said it regrets the incident took place and has updated equipment and management processes, as well as increased inspections and training for operators in the region.

“When this overflow occurred, the water quickly froze and all impacted snow and ice from the area was removed,” the statement said. “No water from this overflow entered any rivers and there continues to be no indication of adverse impacts to local wildlife.”

Communities downstream of the oilsands have disproportionately high rates of rare cancers, like bile-duct cancer. Years of advocacy and whistleblowing finally led to action by Ottawa last summer. In August, the federal government announced a cumulative health study in the region to investigate the harms caused by the heart of Canada’s fossil fuel industry.

“They allowed it to happen,” Adams said of the regulator’s role in the Kearl spill.

“That’s the one thing that the public has to be aware of — they are responsible for more than you think.”

— with files from Natasha Bulowski

Matteo Cimellaro / Canada’s National Observer / Local Journalism Initiative