LAKELAND - Checking 700 cows on open and wooded pastureland is a time intensive process, but advances in drone technology are saving hours for Jay Cory and his kids.

Cory runs a mixed crop-cattle farm south of Ardmore. He and his father, Neil, breed Charolais and Red Angus cows and pasture them on quarter sections near Ardmore, Cold Lake, Elizabeth Métis Settlement, and Lac La Biche. His son Jacob and daughter Isabella are both studying at the University of Saskatchewan but help on the farm when they are home on breaks.

Cory now has three drones that he uses on his farm.

“Using the drone, you can easily check a couple of quarters in say 30 minutes, whereas if you’re riding around on a horse or a quad it would take probably two or three hours to check the area,” said Cory.

Transport Canada regulations require drones to remain in the operator’s line of sight while they are being flown unless special permission has been given, and for the operator to have a drone piloting license. New regulations coming in to effect this fall are expected to loosen the restrictions around beyond-visual-line-of-sight flights.

Cory’s drone experience started last spring with an agricultural drone used for seeding his cover crops.

“This way I don’t have to drive a tractor through there and squish the corn down with the tires. It’s easier to use the drone because it doesn’t leave any tracks in the field. I also used it to seed pastureland, because pastureland is pretty rough and bumpy and it’s hard to drive equipment in those areas,” explained Cory.

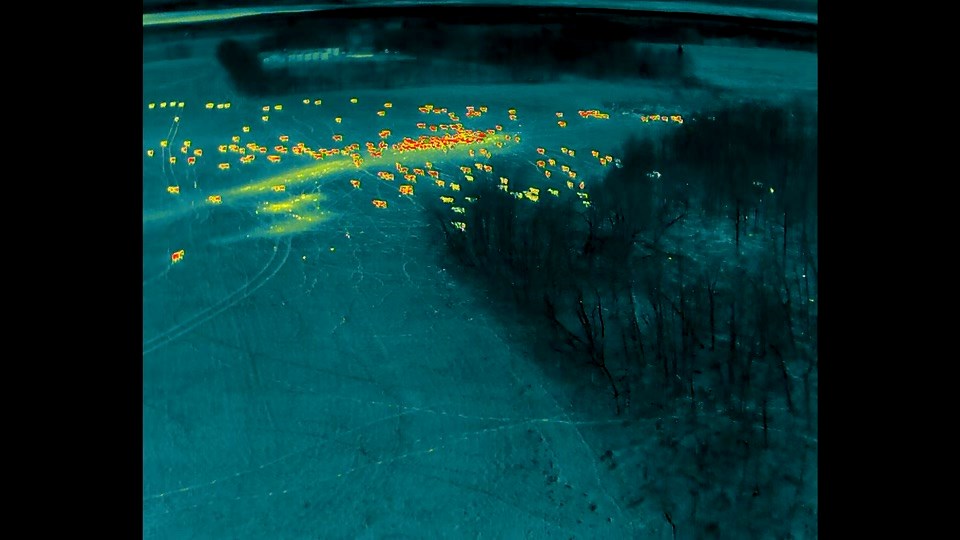

Cory used another small drone with a camera mounted on it to map for the seeding drone and experimented using it to look for cows. He said he had difficulty spotting the cattle through the trees with the mapping drone, so he got a third one in November, which has a thermal camera, 20x optical zoom, and 200x digital zoom.

“You can see through the trees because of the thermal camera, so it really makes it a lot easier that way.”

Cory adds, “You can even herd them a little bit with the drone. If you come down low, they don’t really like it that much and you can move them a bit.”

He said one of the challenges of using the drone to move the cows is battery life. Cattle don’t move quickly, so sometimes the drone is running out of power before the job is done.

Another concern Cory has about drones is the increasing tensions with China. He said not only are the drones he has all manufactured in China, but there is no North American made equivalent available on the market.

“There's a few people that assemble drones, and they're kind of made in the US, but all the parts come from China. So, I worry about if we'll have access to them eventually,” said Cory.

“The other thing is, it's technology, right? In three years, there’ll be something better, and they won't be worth anything.”

Cory said he doesn’t think the drones will remove the need for people to check on cows, especially in the spring when they’re calving.

“When we're in the height of calving, we'll have 20 to 30 calves a day. So, some are going to be fine, and some are going to have trouble . . . So there's always somebody watching those cattle. You definitely want to make sure that if they need help, they get help.”

Where the drone will help this spring he said, is in spotting the cows and their newborn calves when they are far away from the rest of the herd.