Nancy Hollman remembers sitting on her dad’s knee, listening to him tell stories of a Metis heritage that now faces extinction.

“Cree is a dying language. It would be devastating to lose our Cree. It’s a beautiful language. And what’s our culture without Cree? The loss of Cree means a loss of identity for the Metis People,” said Hollman, who teaches Cree at the Native Friendship Centre and at Central Elementary School in Lac La Biche.

In a history that has been passed down from generation to generation through storytelling, the few Cree-speaking elders remaining are now unable to share their heritage with Metis youth.

“Cree history is mostly oral and there are not that many elders left to share it,” said Hollman, whose first language was Plains Cree, as her parents were not fluent in English. “I could probably count on one hand how many elders in the area speak the language.”

Hollman, who is the youngest of 13 siblings, attributes the declining use of Cree in part to the shame the Metis people suffered in Canada’s residential schools.

“People in residential schools were forced to speak English and were punished for speaking Cree. And some of that shame is still evident in the adults.”

Though the issue affects a heritage beyond the borders of Lac La Biche County, one of the first and most widely used Cree dictionaries was written by Emily Hunter of Goodfish Lake, said Hollman.

Nicole Lugosi, a Cree Language Instructor at the University of Alberta, said losing the more than 10,000-year-old language would not only starve the world of a culturally significant way of thinking but also sever the Metis people from their rich ancestry.

“I certainly think the language is threatened. Culture is embedded in language, not only in terms of the words and concepts, but the entire worldview about the land, people, relationships, spirituality and ways of thinking,” said Lugosi. “As each culture, and therefore language, is unique, loss of language affects identity by disconnecting people from their unique ancestral backgrounds, teachings and philosophies.”

While there are limited resources that teach the many dialects of Cree including Mitchif, Lugosi maintains that the key to keeping the language alive is teaching the language and its traditional expression through syllabics to children and adults.

“Cree is widely spoken, [but] there remains limited resource materials,” she said. “Those creating programs to teach Cree in the community must also focus on building adult literacy and skills. What often happens is a strong focus on teaching children Cree, which is wonderful, but many children have no one to speak it with to maintain and build those skills.”

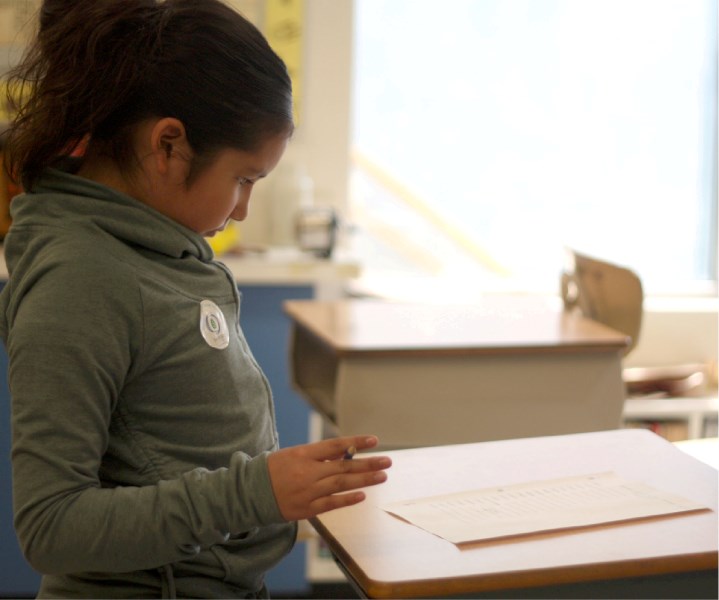

Unknowingly tasked with helping preserve a dying language, Lyric Lewis, a nine-year-old Plains Cree student in Hollman’s class, says she loves learning the language.

“My kookum is proud of me,” said Lewis, adding that she’s excited to be able to speak Cree with her parents. “My parents only speak Cree when they don’t want me to hear.”