COMPTON, Calif. (AP) — Math is the subject sixth grader Harmoni Knight finds hardest, but that's changing.

In-class tutors and “data chats” at her middle school in Compton, California, have made a dramatic difference, the 11-year-old said. She proudly pulled up a performance tracker at a tutoring session last week, displaying a column of perfect 100% scores on all her weekly quizzes from January.

Since the pandemic first shuttered American classrooms, schools have poured federal and local relief money into interventions like the ones in Harmoni's classroom, hoping to help students catch up academically following COVID-19 disruptions.

But a new analysis of state and national test scores shows the average student remains half a grade level behind pre-pandemic achievement in both reading and math. In reading, especially, students are even further behind than they were in 2022, the analysis shows.

Compton is an outlier, making some of the biggest two-year gains in both subjects among high-poverty districts. And there are other bright spots, along with evidence that interventions like tutoring and summer programs are working.

The Education Recovery Scorecard analysis by researchers at Harvard, Stanford and Dartmouth allows year-to-year comparisons across states and districts, providing the most comprehensive picture yet of how American students are performing since COVID-19 first disrupted learning.

The most recent data is based on tests taken by students in spring 2024. By then, the worst of the pandemic was long past, but schools were dealing still with a mental health crisis and high rates of absenteeism — not to mention students who'd had crucial learning disrupted.

“The losses are not just due to what happened during the 2020 to 2021 school year, but the aftershocks that have hit schools in the years since the pandemic,” said Tom Kane, a Harvard economist who worked on the scorecard.

In some cases, the analysis shows school districts are struggling when their students may have posted decent results on their state tests. That’s because each state adopts its own assessments, and those aren’t comparable to each other. Those differences can make it impossible to tell whether students are performing better because of their progress, or whether those shifts are because the tests themselves are changing, or the state has lowered its standards for proficiency. For example, Wisconsin, Nebraska and Florida seem to have relaxed their proficiency cutoff in both math and reading in the last two years, Kane said, citing the analysis.

The Scorecard accounts for differing state tests and provides one national standard.

Higher-income districts have made significantly more progress than lower-income districts, with the top 10% of high-income districts four times more likely to have recovered in both math and reading compared with the poorest 10%. And recovery within districts remains divided by race and class, especially in math scores. Test score gaps grew by both race and income.

“The pandemic has not only driven test scores down, but that decline masks a pernicious inequality that has grown during the pandemic,” said Sean Reardon, a Stanford sociologist who worked on the scorecard. “Not only are districts serving more Black and Hispanic students falling further behind, but even within those districts, Black and Hispanic students are falling further behind their white district mates.”

Tutors in class, after school and on Saturdays

Still, many of the districts that outperformed the country serve predominantly low-income students or students of color, and their interventions offer best practices for other districts.

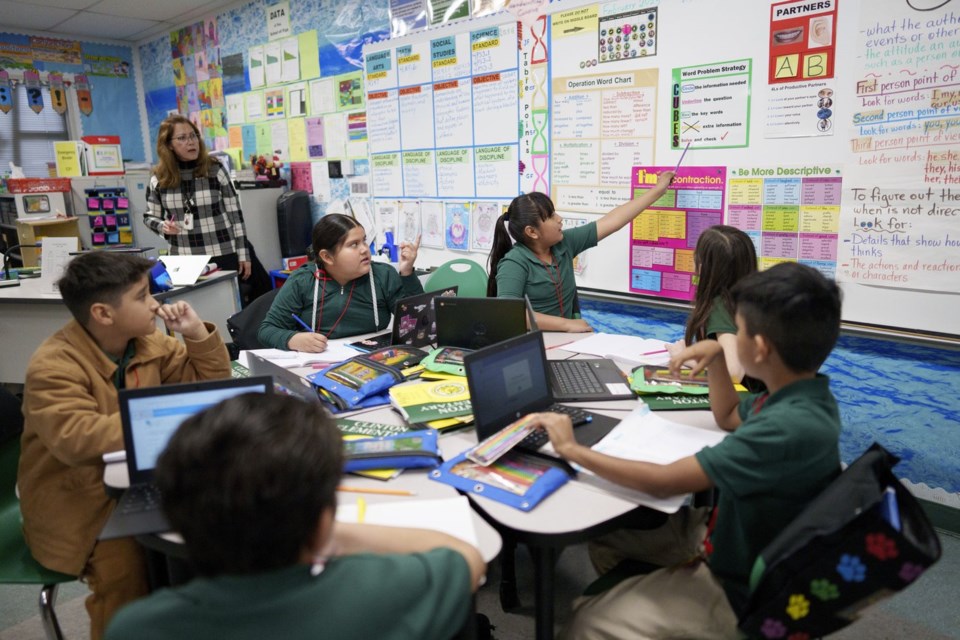

In Compton, the district has responded to the pandemic by hiring over 250 tutors that specialize in math, reading and students learning English. Certain classes are staffed with multiple tutors to assist teachers. And schools offer tutoring before, during and after school, plus “Saturday School” and summer programs for the district’s 17,000 students, said Superintendent Darin Brawley.

To identify younger students needing targeted support, the district now conducts dyslexia screenings in all elementary schools.

The low-income school district near downtown Los Angeles, with a student body that is 84% Latino and 14% Black, now has a graduation rate of 93%, compared with 58% when Brawley took the job in 2012.

Harmoni, the sixth-grader, said that one-on-one tutoring has helped her grasp concepts and given her more confidence in math. She gets separate “data chats” with her math specialist that are part performance review, part pep talk.

“Looking at my data, it kind of disappoints me” when the numbers are low, said Harmoni. “But it makes me realize I can do better in the future, and also now.”

Brawley said he’s proud of the district's latest test scores, but not content.

“Truth be told, I wasn’t happy,” he said. “Even though we gained, and we celebrate the gains, at the end of the day we all know that we can do better.”

As federal pandemic relief money for schools winds down, states and school districts will have limited resources and must prioritize interventions that worked. Districts that spent federal money on increased instructional time, either through tutoring or summer school, saw a return on that investment.

Reading levels have continued to decline, despite a movement in many states to emphasize phonics and the “ science of reading.” So Reardon and Kane called for an evaluation of the mixed results for insights into the best ways to teach kids to read.

The researchers emphasized the need to extend state and local money to support pandemic recovery programs that showed strong academic results. Schools also must engage parents and tell them when their kids are behind, the researchers said.

And schools must continue to work with community groups to improve students' attendance. The scorecard identified a relationship between high absenteeism and learning struggles.

Tutors also help with attendance

In the District of Columbia, an intensive tutoring program helped with both academics and attendance, D.C. Public Schools Chancellor Lewis Ferebee said. In the scorecard analysis, the District of Columbia ranked first among states for gains in both math and reading between 2022 and 2024, after its math recovery had fallen toward the bottom of the list.

Pandemic-relief money funded the tutoring, along with a system of identifying and targeting support at students in greatest need. The district also hired program managers who helped maximize time for tutoring within the school day, Ferebee said.

Students who received tutoring were more likely to be engaged with school, Ferebee said, both from increased confidence over the subject matter and because they had a relationship with another trusted adult.

Students expressed that “I'm more confident in math because I'm being validated by another adult,” Ferebee said. "That validation goes a long way, not only with attendance, but a student feeling like they are ready to learn and are capable, and as a result, they show up differently.”

Federal pandemic relief money has ended, but Ferebee said many of the investments the district made will have lasting impact, including the money spent on teacher training and curriculum development in literacy.

Christina Grant, who served as the District of Columbia's state superintendent of education until 2024, said she's hopeful to see the evidence emerging on what's made a difference in student achievement.

“We cannot afford to not have hope. These are our students. They did not cause the pandemic,” Grant said. “The growing concern is ensuring that we can ... see ourselves to the other side.”

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Annie Ma And Jocelyn Gecker, The Associated Press