When Maryam Jillani was growing up in Islamabad, the last day of Ramadan was about more than breaking a month-long fast with extended family.

A joyous occasion, the Eid al-Fitr holiday also was marked with visits to the market to get new bangles, wearing her best new clothes and getting hennaed. Not to mention the little envelopes with cash gifts from the adults.

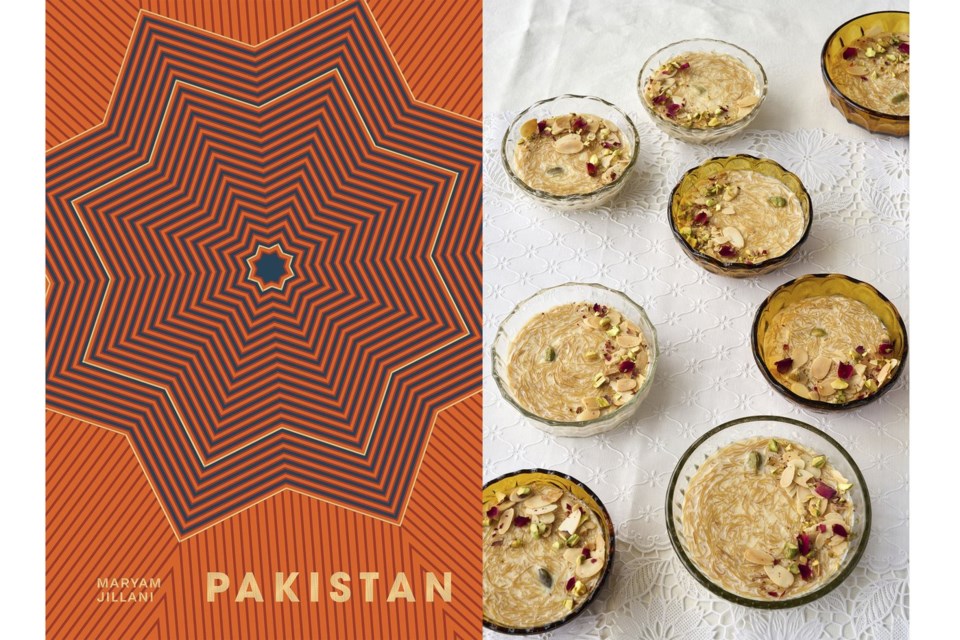

“But, of course, food,” said Jillani, a food writer and author of the new cookbook “Pakistan.” “Food is a big part of Eid.”

At the center of her grandmother Kulsoom’s table was always mutton pulao, a delicately spiced rice dish in which the broth that results from cooking bone-in meat is then used to cook the rice. Her uncle would make mutton karahi, diced meat simmered in tomato sauce spiked with ginger and chilies.

Cutlets, kebabs, lentil fritters and more rounded out the meal, while dollops of pungent garlic chutney and a cooling chutney with cilantro and mint cut through all the meat. For dessert were bowls of chopped fruit and seviyan, or semolina vermicelli noodles that are fried then simmered in cardamom-spiced milk.

The vegetable sides were the one thing that changed. Since Ramadan follows the lunar Islamic calendar, it can fall any time of year.

These dishes, and many of the associated memories, make it into Jillani’s book, but she would be the first to acknowledge they represent just a sliver of the nation’s varied cuisine.

Her father, who worked in international development, used to take the family to different parts of the country. Later, she did her own development fieldwork in education across rural Pakistan.

Along the way, she found striking differences between the tangier, punchier flavors in the east, toward India and China, and the milder but still flavorful cuisine in the west, toward Afghanistan.

“I knew our cuisine was a lot more than what we were finding on the internet,” she said.

After moving to Washington, D.C. as a graduate student, she started the blog Pakistan Eats in 2008 to highlight dishes that were lesser known to Western cooks. Research on the book began 15 years later, and she visited 40 kitchens in homes across Pakistan.

“Even though I hadn’t lived in Pakistan for over 10 years, each kitchen felt like home,” she writes in the book's introduction.

She includes what she calls “superstars” of the cuisine, such as chicken karahi, one of the first dishes Pakistanis learn to make when overseas to get a taste of home. The meat is seared in a karahi (skillet) and then braised in a tomato sauce spiced with cumin, coriander, ginger, garlic and chilies before a dollop of yogurt is stirred into the pot.

Other recipes reflect the diverse nature of Pakistan’s migrant communities, such as kabuli pulao, an Afghan rice dish made with beef, garam masala, chilies, sweetened carrots and raisins.

“The idea behind the cookbook is to try to play my small part in carving out a space for Pakistani food on the global culinary table,” she said.

And of course, honoring her grandmother’s mutton pulao.

Jillani is hosting Eid this year at her home, now in Manila, Philippines, and she plans to make it, as well as an Afghan-style eggplant, shami kebabs, and the cilantro and mint chutney.

“If I’m feeling especially ambitious that day, I might make a second mutton dish,” she said. “I’ve been a bit homesick.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Albert Stumm writes about food, travel and wellness. Find his work at https://www.albertstumm.com

Albert Stumm, The Associated Press