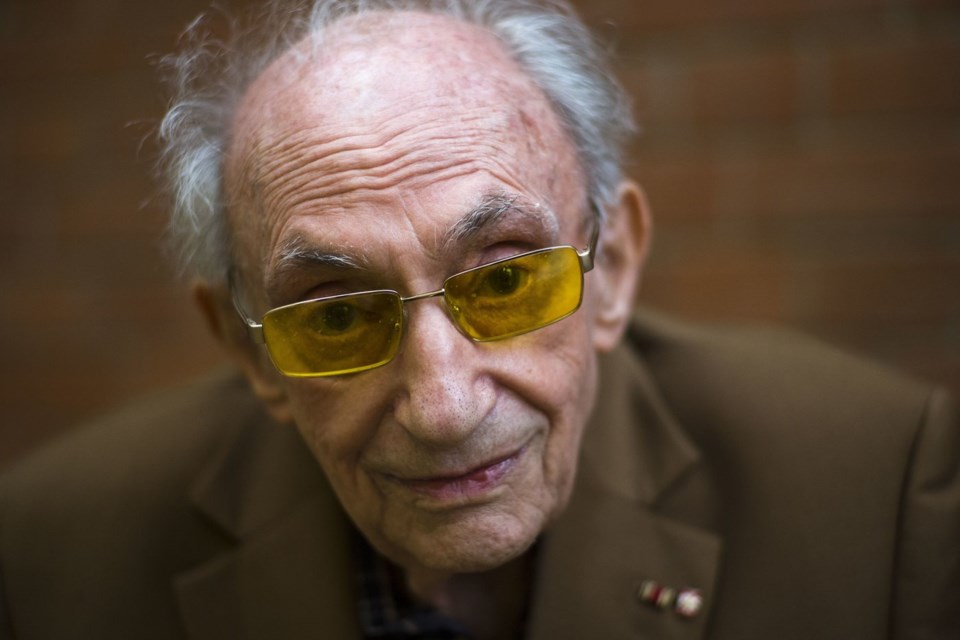

BERLIN (AP) — Walter Frankenstein, who survived the Holocaust by hiding in Berlin with his wife and infant children and spent his later years educating young people to keep the events alive in memory, has died. He was 100.

Klaus Hillenbrand, a close friend who wrote a book about Frankenstein, confirmed the death on Tuesday. He said Frankenstein died on Monday. The foundation that oversees Berlin's Holocaust memorial also confirmed that he died Monday in Stockholm.

Frankenstein was born in 1924 in Flatow in what is now Poland but was then part of Germany. Three years after the Nazis came to power, in 1936, he was no longer allowed to attend the town’s public school because he was Jewish.

With the help of an uncle, his mother sent him to Berlin where he could continue his school education, and he later trained as a bricklayer at the Jewish community’s vocational school. He stayed at the Jewish Auerbach’sche Orphanage where he met Leonie Rosner, who would later become his wife.

In an interview with The Associated Press in 2018, Frankenstein described how he witnessed Kristallnacht — the “Night of Broken Glass” on November 9, 1938, when Nazis, among them many ordinary Germans, terrorized Jews throughout Germany and Austria. They killed at least 91 people and vandalized 7,500 Jewish businesses. They also burned more than 1,400 synagogues, according to Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial. Up to 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and taken to concentration camps.

Frankenstein, who was then 14, climbed on the roof of the orphanage and saw fire lighting up the city.

“Then we knew: the synagogues were burning,” he said. “The next morning, when I had to go to school, there was sparkling, broken glass everywhere on the streets.”

Starting in 1941, Frankenstein had to do forced labor in Berlin, repeatedly threatened by the danger of being deported by the Nazis.

In 1943, five weeks after their son Peter-Uri was born, he went into hiding with his wife, Leonie, as the Nazis were deporting thousands of Jews from Berlin to Auschwitz.

“We had promised ourselves not to do what Hitler wanted,” Frankenstein told the AP. “So we went into hiding.”

Together with their baby, the couple spent 25 months in hiding in Berlin. A second son, Michael, was born in 1944, during their time on the run. They stayed with friends or in bombed-out buildings.

Up to 7,000 Berlin Jews had gone into hiding, but only 1,700 of them were able to survive. The others were either arrested, died of illness or perished in air raids.

In 1945, when Berlin was liberated by the Soviet Red Army, Frankenstein’s children were among the youngest of a total of only 25 Jewish children who had survived in Berlin.

Before the Holocaust, Berlin had the biggest Jewish community in Germany. In 1933, the year the Nazis came to power, around 160,500 Jews lived in Berlin. By the end of World War II in 1945 their numbers had diminished to about 7,000 through emigration and extermination.

All in all, some 6 million European Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.

After the collapse of the Nazis’ Third Reich, the Frankensteins immigrated to what was then Palestine and later became Israel. Eleven years later, in 1956, they moved to Sweden, where they settled for good.

Later in life, Walter Frankenstein returned to Germany several times a year. He often talked to schoolchildren about his life and in 2014, he received Germany’s highest honor, the Order of Merit.

He was also an ardent fan of the Hertha Berlin soccer club. As a teenager he went to its games, and when Jews were no longer allowed to visit the stadium he would listen to reports of matches on the radio. In 2018, Frankenstein became an honorary member of the club with the membership number 1924, his year of birth.

Every time Frankenstein traveled to Berlin in his later years, he brought along the small blue case containing the Order of Merit. Inside the case’s lid, he had attached the first “mark” he got from the Germans: the yellow badge, or Jewish star, that he had to wear during the Nazi reign to identify him as a Jew.

“The first one marked me, the second one honored me,” he said.

Kirsten Grieshaber, The Associated Press