VIRGINIA BEACH, Va. (AP) — Pat Robertson, a religious broadcaster who turned a tiny Virginia station into the global Christian Broadcasting Network, tried a run for president and helped make religion central to Republican Party politics in America through his Christian Coalition, has died. He was 93.

Robertson's death Thursday was confirmed in an email by his broadcasting network. No cause was given.

Robertson’s enterprises also included Regent University, an evangelical Christian school in Virginia Beach; the American Center for Law and Justice, which defends the First Amendment rights of religious people; and Operation Blessing, an international humanitarian organization.

For more than a half-century, Robertson was a familiar presence in American living rooms, known for his “700 Club” television show, and in later years, his televised pronouncements of God’s judgment, blaming natural disasters on everything from homosexuality to the teaching of evolution.

The money poured in as he solicited donations, his influence soared, and he brought a huge following with him when he moved directly into politics by seeking the GOP presidential nomination in 1988.

Robertson pioneered the now-common strategy of courting Iowa’s network of evangelical Christian churches, and finished in second place in the Iowa caucuses, ahead of Vice President George H.W. Bush.

His masterstroke was insisting that three million followers across the U.S. sign petitions before he would decide to run, Robertson biographer Jeffrey K. Hadden said. The tactic gave him an army.

″He asked people to pledge that they’d work for him, pray for him and give him money,” Hadden, a University of Virginia sociologist, told The Associated Press in 1988. ″Political historians may view it as one of the most ingenious things a candidate ever did.″

Robertson later endorsed Bush, who won the presidency. Pursuit of Iowa’s evangelicals is now a ritual for Republican hopefuls, including those currently seeking the White House in 2024.

Robertson started the Christian Coalition in Chesapeake in 1989, saying it would further his campaign’s ideals. The coalition became a major political force in the 1990s, mobilizing conservative voters through grass-roots activities.

By the time of his resignation as the coalition's president in 2001 — Robertson said he wanted to concentrate on ministerial work — his impact on both religion and politics in the U.S. was “enormous,” according to John C. Green, an emeritus political science professor at the University of Akron.

Many followed the path Robertson cut in religious broadcasting, Green told the AP in 2021. In American politics, Robertson helped “cement the alliance between conservative Christians and the Republican Party.”

Marion Gordon “Pat” Robertson was born March 22, 1930, in Lexington, Virginia, to Absalom Willis Robertson and Gladys Churchill Robertson. His father served for 36 years as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Virginia.

After graduating from Washington and Lee University, he served as assistant adjutant of the 1st Marine Division in Korea.

He received a law degree from Yale University Law School, but failed the bar exam and chose not to pursue a law career.

Robertson met his wife, Adelia “Dede” Elmer, at Yale in 1952. He was a Southern Baptist, she was a Catholic, earning a master’s in nursing. Eighteen months later, they ran off to be married by a justice of the peace, knowing neither family would approve.

Robertson was interested in politics until he found religion, Dede Robertson told the AP in 1987. He stunned her by pouring out their liquor, tearing a nude print off the wall and declaring he had found the Lord.

They moved into a commune in New York City’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood because Robertson said God told him to sell all his possessions and minister to the poor. She was tempted to return home to Ohio, “but I realized that was not what the Lord would have me do ... I had promised to stay, so I did,” she told the AP.

Robertson received a master’s in divinity from New York Theological Seminary in 1959, then drove south with his family to buy a bankrupt UHF television station in Portsmouth, Virginia. He said he had just $70 in his pocket, but soon found investors, and CBN went on the air on Oct. 1, 1961. Established as a tax-exempt religious nonprofit, CBN brought in hundreds of millions, disclosing $321 million in “ministry support” in 2022 alone.

One of Robertson’s innovations was to use the secular talk-show format on the network’s flagship show, the “700 Club,” which grew out of a telethon when Robertson asked 700 viewers for monthly $10 contributions. It was more suited to television than traditional revival meetings or church services, and gained a huge audience.

“Here’s a well-educated person having sophisticated conversations with a wide variety of guests on a wide variety of topics,” said Green, the University of Akron political science professor. “It was with a religious inflection to be sure. But it was an approach that took up everyday concerns.”

His guests eventually included several U.S. presidents — Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump.

At times, his on-air pronouncements drew criticism.

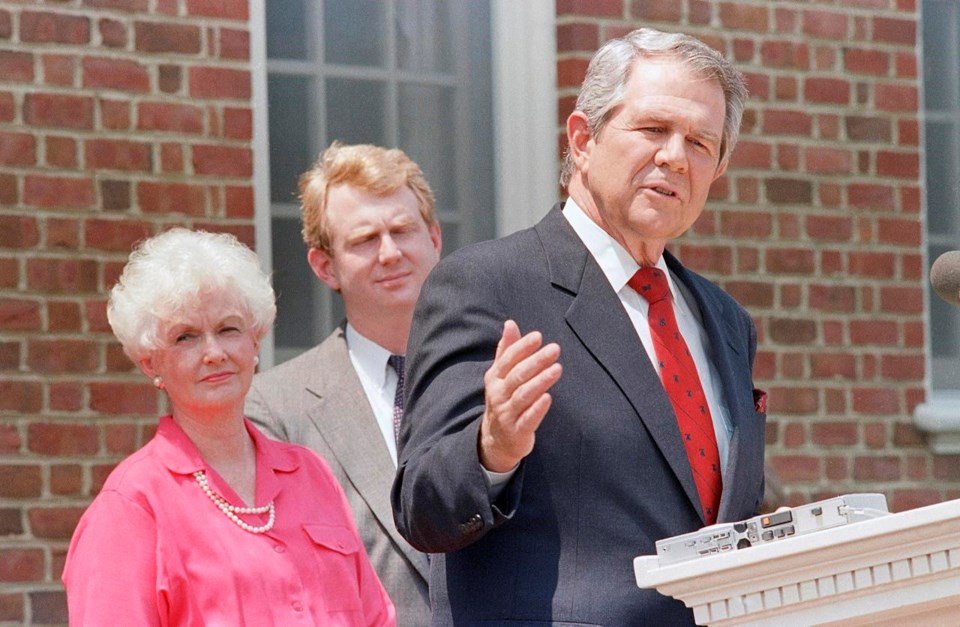

He claimed that the terrorist attacks that killed thousands of Americans on Sept. 11, 2001 were caused by God, angered by the federal courts, pornography, abortion rights and church-state separation. Talking again about 9-11 on his TV show a year later, Robertson described Islam as a violent religion that wants to “dominate” and “destroy,” prompting President George W. Bush to distance himself and say Islam is a peaceful and respectful religion.

He called for the assassination of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez in 2005, although he later apologized.

Later that year, he warned residents of a rural Pennsylvania town not to be surprised if disaster struck them because they voted out school board members who favored teaching “intelligent design” over evolution. And in 1998, he said Orlando, Florida, should beware of hurricanes after allowing the annual Gay Days event.

In 2014, he angered Kenyans when he warned that towels in Kenya could transmit AIDS. CBN issued a correction, saying Robertson “misspoke about the possibility of getting AIDS through towels.”

Robertson also could be unpredictable: In 2010, he called for ending mandatory prison sentences for marijuana possession convictions. Two years later, he said on the “700 Club” that marijuana should be legalized and treated like alcohol because the government’s war on drugs had failed.

Robertson condemned Democrats caught up in sex scandals, saying for example that President Bill Clinton turned the White House into a playpen for sexual freedom. But he helped solidify evangelical support for Donald Trump, dismissing the candidate's sexually predatory comments about women as an attempt “to look like he’s macho.”

After Trump took office, Robertson interviewed the president at the White House. And CBN welcomed Trump advisers, such as Kellyanne Conway, as guests.

But after President Trump lost to Joe Biden in 2020, Robertson said Trump was living in an “alternate reality” and should “move on,” news outlets reported.

Robertson’s son, Gordon, succeeded him in December 2007 as chief executive of CBN, which is now based in Virginia Beach. Robertson remained chairman of the network and continued to appear on the “700 Club.”

Robertson stepped down as host of the show after half a century in 2021, with his son Gordon taking over the weekday show.

Robertson also was founder and chairman of International Family Entertainment Inc., parent of The Family Channel basic cable TV network. Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. bought IFE in 1997.

Regent University, where classes began in Virginia Beach in 1978, now has more than 30,000 alumni, CBN said in a statement.

Robertson wrote 15 books, including “The Turning Tide” and “The New World Order.”

His wife Dede, who was a founding board member of CBN, died last year at the age of 94. The couple had four children, 14 grandchildren and 24 great-grandchildren, CBN said in a statement.

____

Former Associated Press reporters Don Schanche and Pam Ramsey contributed to this story.

Ben Finley, The Associated Press