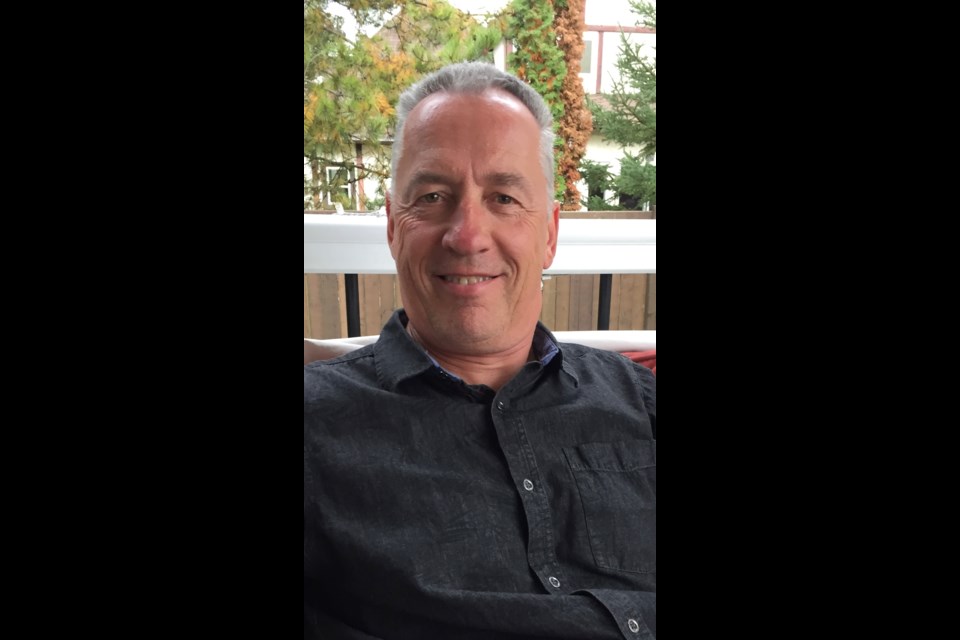

LAKELAND - Bill Buryn knows his cancer will kill him one day. After years of chemo treatments and a stem cell transplant, his cancer cells are at a low enough level to say he’s in remission, but it’s only a matter of time before it comes back.

“I know it’s coming. My oncologist reminds me every time we talk that we have more battles to deal with next time. So that’s hard,” said Buryn.

Buryn, 62, was diagnosed with stage 4 mantle cell lymphoma in June 2021 after noticing he was feeling especially fatigued and had lost about 20 pounds in a single month. He was three years in to being part of the ownership and management team at Zarowny Motors, where he had worked as a car salesman for 38 years.

“I thought, I better get checked because we had some heart disease in the family history. I thought maybe I had a little blockage,” said Buryn. “By the time I left an hour later, I was told I had some kind of cancer and that I was to go home and not go back to work. That was kind of a crusher.”

According to the Cleveland Clinic, mantle cell lymphoma is a rare blood cancer that starts in the white blood cells in the lymph nodes. It affects roughly one in 200,000 people, typically aged 60 or older, with men being three times as likely as women to develop it.

Chemo and transplant

A few weeks later, Buryn had a bone biopsy and by August 2021 he started chemotherapy.

“I had six chemo treatments every three weeks. They had to get me back in line. Then I rested for six months and then I went in to the Cross [Cancer Institute] for 32 days to have a stem cell transplant.”

Stem cell transplants for lymphoma can be done either using cells collected from the person receiving the transplant, or cells from a matched donor. Buryn opted to use his own cells because it was quicker than waiting for a donor.

“Because they can’t treat everything, I ended up with 99.9 per cent of my blood cells being healthy, but there’s small little bits that are still there. And they’re going to grow as time goes and come back,” said Buryn.

The expectation from doctors is three to five years of remission before further treatment is needed.

“It could come out of remission slowly, or it could come out aggressively. If it’s aggressive, the treatment program is much different than if it’s slowly. So I’m living my life on pins and needles,” said Buryn.

In remission, but always at risk

In December 2022 Buryn was told he was in remission and went on to what’s called a maintenance chemo program with treatments every three months for the next two years.

“They let you heal a little bit, then they poison you again with chemo and it kills more cells, then slowly you heal a little bit and then they stun your system again,” said Buryn.

Because of the toxicity of the chemotherapy drugs and the stem cell transplant, Buryn’s immune system doesn’t have any antibodies to fight off other infections. He needs to receive all his childhood vaccines again but can’t receive the ones made from a live virus, like measles, until he’s a year out from chemo.

“You want to try and do things, except every time I leave the house, I’m taking the risk of catching something that might not be serious, except my body can’t handle it,” said Buryn.

He was hospitalized in the intensive care unit in Grande Prairie after a hunting trip and again in South Dakota during a road trip.

“I went from being a guy who was meeting 10, 15, 20 people a day and worked with 55 people, like a lot of social activity. But that got shut down. That’s what I really miss the most is being able to visit with people.”

Thankful for family support

Buryn said he’s thankful to have a large family who are able to be present for him. His four children are all “partnered up” and he has four grandchildren and another on the way. His extended family includes four living siblings, as well as their spouses, children, and grandchildren.

“Somebody’s always checking in or texting, calling and saying ‘how you doing?’ or ‘how about I pick you up and we go for a drive’,” said Buryn, his voice thick with emotion.

As a husband and a father, he struggles with how his cancer diagnosis impacts his wife Barb and their family.

“I catch them tearing up and crying when they look at me. You know they’re hurting. And even though it’s been quite successful for me, it’s still not easy, because you know you can not beat this thing” said Buryn. “Everything we’re doing is to buy time.”

Asked what he would tell someone newly facing their own diagnosis, Buryn said to be reassured everyone involved in cancer treatment is incredibly professional and supportive.

“Living life with cancer is a very challenging opportunity. It’s hard many days to find some positives from it. But there are some,” said Buryn.