It’s been over a week since roughly 32 First Nation, Métis and Inuit delegates from across the country met with Pope Francis, the head of the Roman Catholic Church, in the Vatican City. On April 1, Pope Francis delivered an apology about the role the church played in the residential school system.

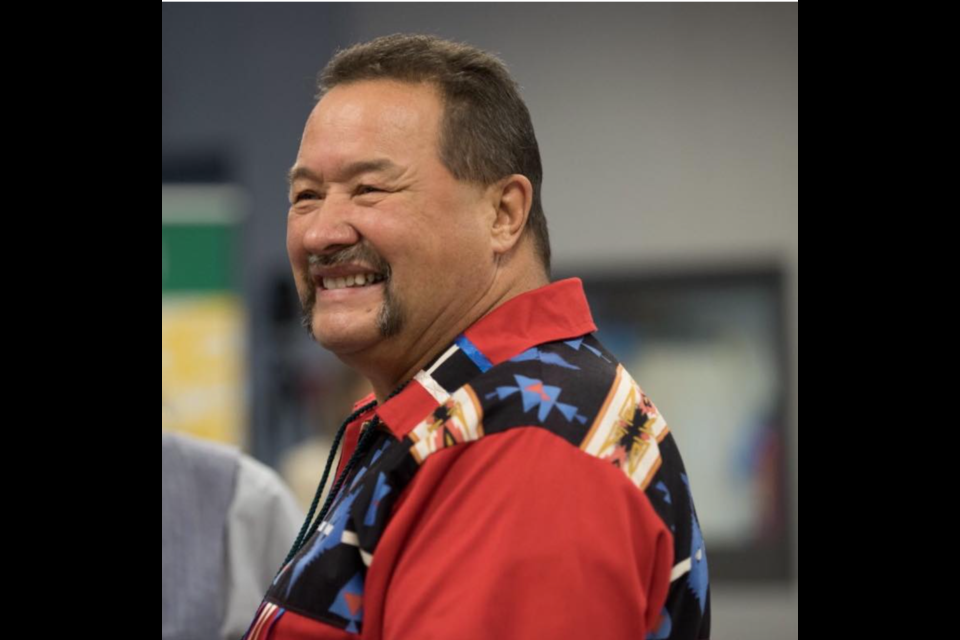

When considering the “trauma that the system has caused” for over 100 years, the President of the Métis Nation of Alberta (MNA) Region 1 James Cardinal, says that although an apology is welcome, and it may be enough for some, it is not enough for everyone to truly heal from the impact.

Cardinal says there is much more work that needs to be done to acknowledge the history of generational trauma and the “major role” the Catholic Church played. Ultimately, it isn’t justified by an apology or “words," he says.

“When someone takes your language away, that’s genocide. When someone takes your culture and your land away that’s genocide…The day they admit all of that, that’s when truth and reconciliation can start.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which was established in 2008, listed 94 calls to action regarding the residential school system. One of the components of the TRC is an apology from the Catholic Church. The church ran more than 139 residential schools across the country.

Considering the meeting came by request, Cardinal says, “apologies can’t heal you, especially one you have to go and ask for.”

The local MNA has yet to gather the community it represents to discuss the details of the meeting.

“For me, it would be hard to know how each individual truly feels, and until we can speak we won’t know. Some could be receptive and some could be not at all,” he says. But as a leader, watching the conversations that took place between Pope Francis and Indigenous communities, the apology has left him somewhere in the middle.

“I’m caught in between. I’m very respectful to the people who responded well to the apology, but I’m also respectful to the people who believe the apology means nothing and that it will never fix what’s been done,” he said.

There has been financial support provided by the federal government in response to the harms caused by residential schools in the past.

“Some of our people get trapped in the financial support… When you take away a person's culture and life no amount of money will ever fix that. We need to build trust and support.”

Trauma varies

Cardinal, who has been a local representative for hundreds of Métis residents in the area for over three years, says although he didn’t personally attend residential schools himself, many of his family members were products of the “horrific system,” and as a result, it stole many relationships he could have had with some of them.

“My older brothers and sisters attended residential schools, so I was robbed of ever really knowing them. I didn't meet them until I was a teenager… The system affected me in that way, and to this day,” he says.

Cardinal says his siblings attended residential schools near Slave Lake for a number of years in the 1960s.

“We are good friends, we know we’re brothers and sisters now, but it could never be more than acquaintances. I love my siblings - I really do - and I know they’re my family now, but at that time it was kind of hard for me to learn to know I had siblings,” he says.

Responsibilities with leadership

While recalling his own journey, he notes that opinion and experiences are very personal. As a local representative and leader, he has a responsibility to ask the tough questions to support Métis members.

And today, the biggest impact is the discovery of the unmarked graves of Indigenous residential school students, which Cardinal says Pope Francis didn’t “bother to discuss.”

“Not once did he mention the unmarked graves, which is such a sensitive topic at this point. Thousands and thousands of unmarked graves. That would have been a start because that’s the most important right now for the people, even for people who didn’t go to the schools, the unmarked graves still affects us. That apology should have been mentioned.”

Meeting in the middle

Considering that Pope Francis put forward a possible journey to visit Canadian Indigenous communities on behalf of the church during the recent delegations, Cardinal hopes that if the Pope visits the Lac La Biche community, he can be a part of that conversation.

“I’m hoping to be one of the leaders. We as Indigenous people need to start working together to help each other heal. I hope I can be a part of that message."

With time and leadership, a bright future is surely ahead, added Cardinal.

“We are going in the right direction. A few generations ahead, I think we will have some results, but for now it will take time.”

Pope Francis reflects

Speaking earlier this month, Pope Francis said that he was “deeply grieved” to hear of the challenges that Indigenous people have had to face over the centuries.

“It is chilling to think of determined efforts to instill a sense of inferiority, to rob people of their cultural identity, to sever their roots, and to consider all the personal and social effects that this continues to entail: unresolved traumas that have become intergenerational traumas,” he said.

Moving forward, he hopes to work toward reconciling the traumatic relationship, and through a potential visit to the ancestral land of the Indigenous people of Canada, he hopes to forge a learning, positive relationship to support healing, on behalf of the Roman Catholic Church.