Chronic wasting disease (CWD) has been spreading across Canada, with the first-ever case in B.C. detected only last year, and concern is mounting over the harm it could do as it continues to spread among Alberta's deer populations.

It's called "zombie deer disease" for a reason: the affliction is incurable, has a 100 per cent fatality rate in cervids and is believed to be transmissible among different deer species.

With that in mind, experts are working hard to get the spread under control while better understanding its effects.

Debbie McKenzie, an emeritus professor of biological sciences with the University of Alberta who has studied CWD for over 25 years, has been keeping a close eye on the disease's spread.

"This is a problem because as well as the geographic spread, the number of deer in a given area that are infected continues to increase," said McKenzie. "This is just not going to do good things, obviously, to the deer populations."

What is being done about CWD?

The Government of Alberta's monitoring of CWD is conducted through samples taken from deer carcasses, including roadkill and the heads of harvested deer submitted by hunters for analysis.

The latest data available is from the 2023-2024 surveillance season, which shows a total of 708 deer — mule, white-tailed, elk and moose — tested positive for CWD. Almost 19 per cent of deer tested positive for CWD: 576 mule deer (365 males, 211 females), 112 whitetails (92 males, 20 females), 13 elk (four males, nine females) and seven moose (two males, five females).

The total number is lower than findings from preceding years, with 1,156 cases detected in the 2021-2022 season, but substantially higher than the total of four cases detected in 2005.

A grand total of 94 cases were detected from 2005 to 2010, and 578 were detected in 2018.

CWD has been detected in 36 U.S. states and five Canadian provinces: Alberta, Saskatchewan, Québec, Manitoba and B.C.

"When it first showed up in Alberta, all the positive deer were clustered on the Alberta-Saskatchewan border," said McKenzie. "Now it just continuously moves westward, it's moving north, it's up almost to Cold Lake now, it's almost down to the U.S. border."

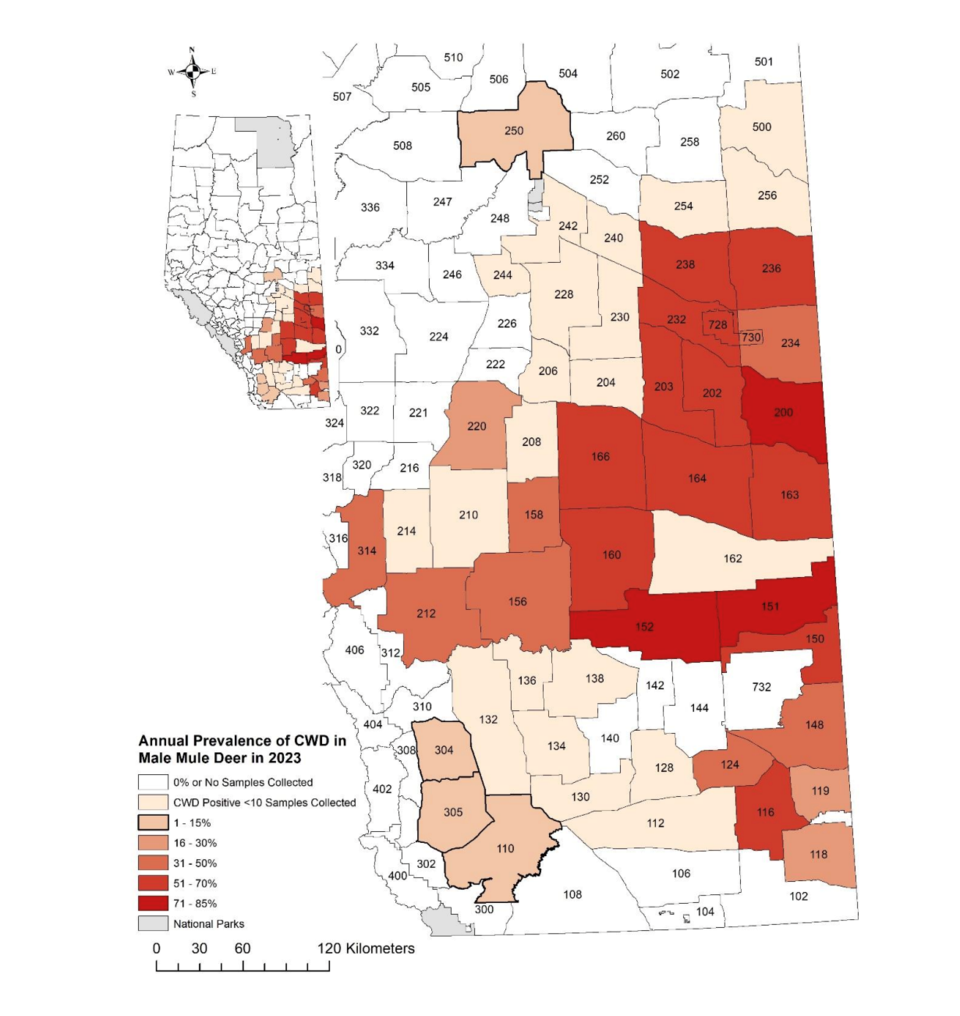

In Alberta, CWD rates in mule deer bucks, which are statistically the most likely deer to be infected, reached up to 85 per cent in some areas near the Saskatchewan border, particularly near the South Saskatchewan River valley.

Canadian Forces Base Wainwright, located west of the Alberta-Saskatchewan border, had the highest overall CWD rate with 70 cases confirmed.

Manitoba, a province that first confirmed the presence of CWD in 2021 and has only detected a total of 30 cases, initiated a large-scale cull in December of 2021 along the Manitoba-Saskatchewan border, with marksmen in helicopters gunning down hundreds of whitetails and mule deer with semi-automatic rifles to prevent any potential spread of the disease.

In B.C., where five cases have been confirmed so far, 200 deer are being killed and tested for CWD in a cull set to take place in the cities of Cranbrook and Kimberley, located near the B.C.-Alberta border. In addition to the cull, which commenced on Feb. 18, a special permitted hunt will take place in the Kootenays to further curb any potential spread of the disease.

While all five CWD-positive deer in B.C. were found in wildlife areas outside of those cities, urban deer are being culled since their high proximity to each other likely puts them at a higher risk of contracting the infectious disease.

"In general, if you can reduce the number of animals when a new positive is found, then you can slow down the transmission rates," said McKenzie. "There was a huge effort when CWD first showed up in Alberta to really reduce the population, but that was pretty unpopular, so that management strategy was stopped."

Towns in Alberta have ruled out culls for now, with municipalities working on other solutions to resolve issues stemming from deer overpopulation in urban areas.

What does CWD mean for deer populations?

All deer with CWD are marked for death.

CWD, which has no vaccine or treatment, can take up to three years to have visible effects on an infected animal. As the disease progresses, animals will excessively salivate and become emaciated as their central nervous systems are destroyed.

Despite its invariable fatality rate and infectious nature, there have not yet been any cases of an entire deer population being eradicated by the disease, said McKenzie.

"We don't really know what the potential long-term effects could be on various deer herds," she said.

"There's evidence from a number of different places in Canada and the U.S. that shows that once the number of infected animals gets above 30 per cent, particularly in the females, that populations start to decline."

As infected animals usually take a few years to die from the disease – females with CWD are able to reproduce within that time – likely balancing out the population.

While mule deer are the most likely to contract CWD, concern is growing over its impact on other deer species.

The first-ever Canadian case of CWD in a moose was confirmed in 2012 near the South Saskatchewan River valley in southern Alberta, an area overlapping with infected mule and white-tailed deer populations.

In the 2023-2024 surveillance season, seven moose, or 3.1 per cent of the 223 tested, were found to have CWD.

That may seem like a low number, but it represents a significant increase in infection rates among moose: there were zero cases detected in the 2021-2022 season and five in 2022-2023.

As cervids, caribou are considered to be at risk of contracting CWD, though research suggests that some caribou may be less susceptible to the disease.

While there is currently no evidence of CWD in any Canadian caribou, it remains a major concern, as according to the Government of Alberta there are only 16 caribou populations in the province.

With caribou considered a threatened species, CWD would only be another factor contributing to their decline, adding on to the devastating effects that environmental factors like habitat destruction have had on their numbers.

Can CWD harm humans?

The effects of CWD on non-cervid species are still being studied, but for now there have been no proven effects of the disease on humans.

We aren't out of the woods yet though, stressed McKenzie.

"There is no known risk to humans, but we don't know that the risk is zero," she said.

"We don't have a good idea yet on how [CWD] might be spread... either one deer to another deer or from deer to some other species."

Many questions remain around the spread of the disease, which is contracted through proteins called prions rather than a virus.

"What happens is we all have a normal form of the prion protein in our bodies," explained McKenzie. "When an animal or a person gets infected with a prion, then the infectious prion converts the normal cellular protein to the bad form, and that's how it then moves through the brain. As it deposits in the brain, it triggers changes in the functioning of the brain, a lot of which we don't understand yet, and ultimately results in death of neurons, and then ultimately the death of the animal."

In the lab, it has been demonstrated that rodents like mice and beavers can be susceptible to CWD.

"So is there a possibility that, if you have mice on your property, they're going to eat something that a deer has urinated on and get infected?" pondered McKenzie.

CWD prions can be shed into the environment through the saliva, urine and feces of an infected deer, which has the potential to infect other deer. Scientists are still working to determine how long these contagious traces of the disease can linger in the environment.

"We don't know enough yet about what's happening with CWD in the environment, but our research group has some evidence that suggests that CWD prions can be detected in the soil from the same area three or four consecutive years in a row, so it stays there for a while," said McKenzie.

One such prion disease, commonly known as mad cow disease, is another incurable and fatal affliction that affects bovids. Unlike CWD, mad cow disease has been proven to be transmissible to humans that consume the beef of infected animals.

Mad cow disease's incubation period in humans is incredibly long, potentially taking at least 10 years to present symptoms if contracted through consumption, which McKenzie cites as a factor behind there still possibly being effects of CWD on humans that have yet be discovered.

With that in mind, people should make sure not to eat the venison of infected deer.

"We have no evidence that [CWD] can jump to humans, but the best way of making sure that you don't get infected would be not to eat infected animals," she said.

In urban areas where deer co-exist with humans, there is the potential for deer with CWD to indirectly affect humans in other ways.

"I think there's an increased likelihood of deer acting abnormally, so perhaps an increase in the number of car-deer interactions as the brain function is being affected," suggested McKenzie. "The disease is always going to kill the animal if they don't get hit by a car or shot or something, so there's always the potential for more deer carcasses on the environment, but directly, they shouldn't impact people in any major way."